Converging Brass: Encounters between Balkan Musical Communities and HONK!

by Judith E. Olson

Every year in January, the Zlatne Uste Balkan Brass Band sponsors a music festival in Brooklyn’s Grand Prospect Hall. The Golden Festival draws upwards of 60 bands and 3000 people from all over the US and Europe. Some bands that play here also play at HONK! festivals, including What Cheer? Brigade, Hungry March Band, Veveritse, and Zlatne Uste. Both the Golden Festival and HONK! include a mix of amateur and professional musicians, generally playing for free. The Golden Festival charges admission, but proceeds are donated to relief organizations in the Balkans. Audiences for both events include people of a range of ages and backgrounds with quite a few millennials.

The Golden Festival is now a point of confluence between the relatively recent HONK! movement and a century-old American tradition involving European folk music. In the various spaces of Grand Prospect Hall, dance and music from cultures around the Balkans are displayed. But one can also see these manifestations as reflecting how different generations in the United States have constructed the heritage passed on to them by their parents and older enthusiasts as well as adapting it to new artistic priorities, such as participating in HONK!.

Balkan brass, along with the brass music of New Orleans, is one of the primary repertoires of the musically eclectic HONK! movement. But how did Balkan music come to HONK!? Often even without knowing about it, HONK! shares with and benefits from this older tradition that in the mid-twentieth century emerged as International Folk Dance (IFD). What now constitutes a growing number of bands playing Balkan music, whether or not they are associated with HONK!, has often either developed out of the IFD scene or found and used it for musical material and training in technique and improvisation. This study explores recent stages of development of IFD and shows how the latest stage of the tradition has contributed to the current passion for brass bands and to the enthusiasm for Balkan music in the HONK! community. It is also a study of the interaction of past and present in the emergence of new traditions and the preservation of the old.

International Folk Dance refers to a network of recreational groups built around traditional dance and music, mostly from European countries. While this material has been used in the United States in various educational and social projects at least since the late 19th century, it has included an ever-increasing portion of Balkan music and dance since the 1960s. Throughout its history, IFD has been shaped by the world around it and in response to it. Each generation has recreated the tradition according to their needs and possibilities. In other words, transmission has not been in a straight line. Through personal circumstance, I am involved with music and dance worlds of what I view as three generations of IFD in North America. For this study, I wanted to look at this transmission process while people of my study’s oldest generation are still alive. These participants are in their late eighties and nineties, and the oldest dancer I interviewed is 102 and still active. They came of age around the time of World War II and form the dance group of my husband’s parents. Many were the children of immigrants, or had come to the United States themselves as children or adults.

The second group is my own. The late 1960’s up through the 1970’s fomented folk music revivals amidst countercultural and student protest movements throughout the US and Europe. An upsurge in IFD began, and groups were founded throughout the United States, many meeting on university grounds, which resulted in a fairly well-defined age cohort. I began to dance in 1973 in Colorado and continued in various locations until I moved to New York City.

In the 1990’s, groups grew smaller, and there was much talk and anxiety among participants about a decline of folk dancing and the lack of new, younger participants. However, in the last 15 years or so there has been a surge in interest in Balkan dance music, with the latest wave of Balkan bands and dance fueled by millennials including my children and those of many of my friends from the second wave. This has led to wildly successful music and dance events, such as the Golden Festival. Drawing on the ideas of their parents, these participants have developed a concept of community that encompasses immediate neighborhoods but also the fate of Eastern European musicians and social groups as well as others met through social media. I suggest that there are many factors contributing to this trend including increased accessibility to information and travel, which has fostered a growing cosmopolitan culture in the American Balkan scene. These are some of the elements they have in common with HONK! musicians.

While all three generations are involved in IFD and the music associated with it, they clearly enjoy it in different ways. This essay will explore similarities and differences in music and dance practice across the generations as well as what each group took from the other. As I worked my way deeper into the topic, I began to find differences that went beyond the groups’ occupying separate spaces or tending to hang out with their own ages. Real differences in aesthetics and practice became apparent, and by this point I struggle to see in what ways these groups connect at all despite inter-generational events like Golden Festival. The divergence of these dance/musical communities is reflected by the passion of millennial Balkan musicians for brass bands and the HONK! movement.

Folk Dance History

The history of International Folk Dancing in the United States reflects a vision of a pluralistic society that seeks to find ways to accommodate and benefit from people new to the country. In the nineteenth century, the settlement house movement encouraged new immigrants to share dances as a way to learn to live together within American society while introducing their cultures to Americans already here. After the Civil War, folk dancing was also taken up by the physical education movement, finding its way into community spaces. Folk dance became a part of school curriculum in New York City in the first few years of the twentieth century. As the century progressed, groups like the Folk Festival Council of New York strove to broaden the enjoyment of folk dance, under a mission statement “to give the people of New York an opportunity to enjoy the contributions of foreign-born groups to the folk arts and to keep these arts alive as a vital part of our community life by providing foreign-born people themselves with fine and dignified opportunities for artistic expression.”1

Michael and Mary Ann Herman and their Generation

In inviting new immigrants to share music and dances, there was sometimes a need for interlocutors to organize dance and musical material, help teach, and develop educational resources. Michael and Mary Ann Herman fit into this role, moving easily among various national groups. The New York World’s Fair of 1939 was a transformative event in folk dance, with Nationality Days featuring performances by immigrant dance groups and dancing for all in the American Commons, led by Michael Herman. He reported that 5000 people took part and came away with a mailing list of 1500 people. The Hermans began to hold regular folk dance sessions at St. Mark’s Place with immigrant musicians, Michael’s small ensemble, or Mary Ann at the piano. In 1951, the Hermans created the Folk Dance House, which they maintained until 1970. Michael Herman also published over 300 recordings of immigrant bands.2

Many in my study’s first generation remember dancing with Michael Herman at the 1939 World’s Fair and in the Folk Dance House. Evelyn Halper told me that, at one of the Herman’s events, a man who asked her sister to dance turned out to be Gene Kelly of Singin’ in the Rain and other Broadway musicals and films.3 My husband’s father said he often saw Broadway dancers at folk dance events. This highlights the connection of folk dance at this period in time with stage dance, both with character dances (such as those found in ballets or done by well-known dancers) and folk dance national performing groups.

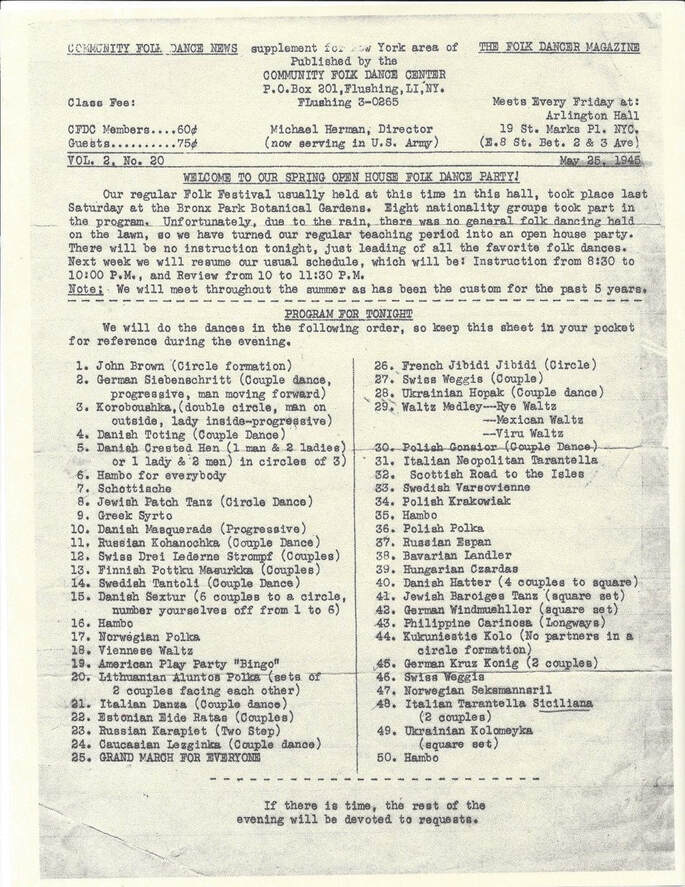

The relationship between folk dancing and specific performance aesthetics changes between the generational cohorts of my study and is one key to understanding their differences. For the first generation, a model of character dances, played out in short pieces and built around characteristic melodies and dance patterns, was common. Evelyn graciously shared with me a program of a folk dance night from this time (Illustration 1). The event was on May 25, 1945 at Arlington Hall at St. Marks Place; the program notes that Michael Herman was serving in the U.S. Army. The evening included 50 dances to be done between 8:30 and 11:30, averaging in time about 3 ½ minutes. Dances are from about 23 nationalities, including the U.S., European countries, Russia, the Ukraine, the Philippines, and Jewish dances. Most dances are denoted by type, and some, such as the hambo or schottische, have a rhythmic pattern to which they are danced. Most, however, have another moniker that indicates that a standard dance is in the form of a choreography (such as the “Kukuniestie Kolo”) or a description, and even those dances with only a designation of nationality (“Ukranian Hopek”) are done in a certain choreography by all dancers. Most dances are for couples, with the exception of an American line dance, a syrto, and one kolo. Evelyn told me that, with many men being in the military, it was less fun for women to dance together as couples, leading to more non-coupled line dances.

Illustration 1. Program for 1945 Folk Dancing Event Sponsored by the Herman’s.

by Judith E. Olson

Every year in January, the Zlatne Uste Balkan Brass Band sponsors a music festival in Brooklyn’s Grand Prospect Hall. The Golden Festival draws upwards of 60 bands and 3000 people from all over the US and Europe. Some bands that play here also play at HONK! festivals, including What Cheer? Brigade, Hungry March Band, Veveritse, and Zlatne Uste. Both the Golden Festival and HONK! include a mix of amateur and professional musicians, generally playing for free. The Golden Festival charges admission, but proceeds are donated to relief organizations in the Balkans. Audiences for both events include people of a range of ages and backgrounds with quite a few millennials.

The Golden Festival is now a point of confluence between the relatively recent HONK! movement and a century-old American tradition involving European folk music. In the various spaces of Grand Prospect Hall, dance and music from cultures around the Balkans are displayed. But one can also see these manifestations as reflecting how different generations in the United States have constructed the heritage passed on to them by their parents and older enthusiasts as well as adapting it to new artistic priorities, such as participating in HONK!.

Balkan brass, along with the brass music of New Orleans, is one of the primary repertoires of the musically eclectic HONK! movement. But how did Balkan music come to HONK!? Often even without knowing about it, HONK! shares with and benefits from this older tradition that in the mid-twentieth century emerged as International Folk Dance (IFD). What now constitutes a growing number of bands playing Balkan music, whether or not they are associated with HONK!, has often either developed out of the IFD scene or found and used it for musical material and training in technique and improvisation. This study explores recent stages of development of IFD and shows how the latest stage of the tradition has contributed to the current passion for brass bands and to the enthusiasm for Balkan music in the HONK! community. It is also a study of the interaction of past and present in the emergence of new traditions and the preservation of the old.

International Folk Dance refers to a network of recreational groups built around traditional dance and music, mostly from European countries. While this material has been used in the United States in various educational and social projects at least since the late 19th century, it has included an ever-increasing portion of Balkan music and dance since the 1960s. Throughout its history, IFD has been shaped by the world around it and in response to it. Each generation has recreated the tradition according to their needs and possibilities. In other words, transmission has not been in a straight line. Through personal circumstance, I am involved with music and dance worlds of what I view as three generations of IFD in North America. For this study, I wanted to look at this transmission process while people of my study’s oldest generation are still alive. These participants are in their late eighties and nineties, and the oldest dancer I interviewed is 102 and still active. They came of age around the time of World War II and form the dance group of my husband’s parents. Many were the children of immigrants, or had come to the United States themselves as children or adults.

The second group is my own. The late 1960’s up through the 1970’s fomented folk music revivals amidst countercultural and student protest movements throughout the US and Europe. An upsurge in IFD began, and groups were founded throughout the United States, many meeting on university grounds, which resulted in a fairly well-defined age cohort. I began to dance in 1973 in Colorado and continued in various locations until I moved to New York City.

In the 1990’s, groups grew smaller, and there was much talk and anxiety among participants about a decline of folk dancing and the lack of new, younger participants. However, in the last 15 years or so there has been a surge in interest in Balkan dance music, with the latest wave of Balkan bands and dance fueled by millennials including my children and those of many of my friends from the second wave. This has led to wildly successful music and dance events, such as the Golden Festival. Drawing on the ideas of their parents, these participants have developed a concept of community that encompasses immediate neighborhoods but also the fate of Eastern European musicians and social groups as well as others met through social media. I suggest that there are many factors contributing to this trend including increased accessibility to information and travel, which has fostered a growing cosmopolitan culture in the American Balkan scene. These are some of the elements they have in common with HONK! musicians.

While all three generations are involved in IFD and the music associated with it, they clearly enjoy it in different ways. This essay will explore similarities and differences in music and dance practice across the generations as well as what each group took from the other. As I worked my way deeper into the topic, I began to find differences that went beyond the groups’ occupying separate spaces or tending to hang out with their own ages. Real differences in aesthetics and practice became apparent, and by this point I struggle to see in what ways these groups connect at all despite inter-generational events like Golden Festival. The divergence of these dance/musical communities is reflected by the passion of millennial Balkan musicians for brass bands and the HONK! movement.

Folk Dance History

The history of International Folk Dancing in the United States reflects a vision of a pluralistic society that seeks to find ways to accommodate and benefit from people new to the country. In the nineteenth century, the settlement house movement encouraged new immigrants to share dances as a way to learn to live together within American society while introducing their cultures to Americans already here. After the Civil War, folk dancing was also taken up by the physical education movement, finding its way into community spaces. Folk dance became a part of school curriculum in New York City in the first few years of the twentieth century. As the century progressed, groups like the Folk Festival Council of New York strove to broaden the enjoyment of folk dance, under a mission statement “to give the people of New York an opportunity to enjoy the contributions of foreign-born groups to the folk arts and to keep these arts alive as a vital part of our community life by providing foreign-born people themselves with fine and dignified opportunities for artistic expression.”1

Michael and Mary Ann Herman and their Generation

In inviting new immigrants to share music and dances, there was sometimes a need for interlocutors to organize dance and musical material, help teach, and develop educational resources. Michael and Mary Ann Herman fit into this role, moving easily among various national groups. The New York World’s Fair of 1939 was a transformative event in folk dance, with Nationality Days featuring performances by immigrant dance groups and dancing for all in the American Commons, led by Michael Herman. He reported that 5000 people took part and came away with a mailing list of 1500 people. The Hermans began to hold regular folk dance sessions at St. Mark’s Place with immigrant musicians, Michael’s small ensemble, or Mary Ann at the piano. In 1951, the Hermans created the Folk Dance House, which they maintained until 1970. Michael Herman also published over 300 recordings of immigrant bands.2

Many in my study’s first generation remember dancing with Michael Herman at the 1939 World’s Fair and in the Folk Dance House. Evelyn Halper told me that, at one of the Herman’s events, a man who asked her sister to dance turned out to be Gene Kelly of Singin’ in the Rain and other Broadway musicals and films.3 My husband’s father said he often saw Broadway dancers at folk dance events. This highlights the connection of folk dance at this period in time with stage dance, both with character dances (such as those found in ballets or done by well-known dancers) and folk dance national performing groups.

The relationship between folk dancing and specific performance aesthetics changes between the generational cohorts of my study and is one key to understanding their differences. For the first generation, a model of character dances, played out in short pieces and built around characteristic melodies and dance patterns, was common. Evelyn graciously shared with me a program of a folk dance night from this time (Illustration 1). The event was on May 25, 1945 at Arlington Hall at St. Marks Place; the program notes that Michael Herman was serving in the U.S. Army. The evening included 50 dances to be done between 8:30 and 11:30, averaging in time about 3 ½ minutes. Dances are from about 23 nationalities, including the U.S., European countries, Russia, the Ukraine, the Philippines, and Jewish dances. Most dances are denoted by type, and some, such as the hambo or schottische, have a rhythmic pattern to which they are danced. Most, however, have another moniker that indicates that a standard dance is in the form of a choreography (such as the “Kukuniestie Kolo”) or a description, and even those dances with only a designation of nationality (“Ukranian Hopek”) are done in a certain choreography by all dancers. Most dances are for couples, with the exception of an American line dance, a syrto, and one kolo. Evelyn told me that, with many men being in the military, it was less fun for women to dance together as couples, leading to more non-coupled line dances.

Illustration 1. Program for 1945 Folk Dancing Event Sponsored by the Herman’s.

The rise of the researcher/teacher was another development of the later post-war period. These researchers would travel to Europe and return with dances, recorded music, and a dance syllabus. Like the dances already being done, these were short, with a crafted piece of music and a set choreography. After developing this repertoire, dance teachers would travel among dance groups throughout the U.S. Often these dances would bear the name of the researcher in the title, as in “Yives invirta,” taught by Yives Moreau. Teachers had varying layers of transparency regarding how they obtained the dances, but often dances were developed for festivals by village dancers, and often they were simplified versions of choreographies by national performing groups.

Researcher/teachers provided a vital service to IFD groups in a time when it was difficult to travel and make contact with European village dancers. The level of trust many teachers received from their students was striking. At dance sessions even now, frequent questions include details regarding where this dance is from, who taught it, and whether the move dancers are doing is actually what was taught by that instructor. In Example 1, Ciuleandra, a dance choreography from the Romanian State Folk Ensemble, modified and taught by Mihai David, is danced at Ellen Golann’s 2015 Holiday Folk Dance Party in Plainview.

Example 1. Ciuleandra danced at Ellen Golann’s Holiday Folk Dance Party Dec 25, 2015.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTcwhD9n8gY>

Illustration 2. Ellen Golann’s Group, Plainview, NY, 23 June 2016 (photo by the author).

Researcher/teachers provided a vital service to IFD groups in a time when it was difficult to travel and make contact with European village dancers. The level of trust many teachers received from their students was striking. At dance sessions even now, frequent questions include details regarding where this dance is from, who taught it, and whether the move dancers are doing is actually what was taught by that instructor. In Example 1, Ciuleandra, a dance choreography from the Romanian State Folk Ensemble, modified and taught by Mihai David, is danced at Ellen Golann’s 2015 Holiday Folk Dance Party in Plainview.

Example 1. Ciuleandra danced at Ellen Golann’s Holiday Folk Dance Party Dec 25, 2015.

<https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTcwhD9n8gY>

Illustration 2. Ellen Golann’s Group, Plainview, NY, 23 June 2016 (photo by the author).

The Hermans’ Folk Dance House and other groups modeled on the idea of a dance leader and regular participants were the start of what many referred to as “the International Folk Dance community.” Participants coming together out of mutual interest often became close friends, first to foster the dance and music they loved, then through hanging out after dancing, but perhaps never visiting each others’ homes. While participation in a group was related to how far one could travel regularly, the sharing of repertoire among groups facilitated by traveling teachers meant that people could drop in on another part of the larger community and feel at home. This sense of community was to expand even further with the development of the second generational group.

Generation Two—The Sixties and Beyond

Most of the people in the second group of dancers, my age group, began dancing on the model of the first, some of them with Michael Herman.4 Many factors contributed to a burst in participation of those coming of age in the late 1960’s and 70’s, including college classes in folk dancing to fulfill a physical education requirement and the ubiquity of dance sessions on college campuses.

Throughout this time, repertoire began to include more line dances and shifted toward the Balkans. This was partly because these dances did not need partners, a boon for both generations, and partly because the derivative choreographies from national performing groups were varied and flashy. Dance researcher/teachers such as Dick Crum, Yives Moreau, and Mihai David presented these dances to receptive groups. The changes also signaled a difference in relationship to the material. With the generational shift to the second group, participants were more distant from their roots and more willing to do dances with which they didn’t have an ancestral connection, but which exerted an emotional pull and helped them to express themselves.5

Many younger New York dancers joined the TOMOV Folk Dance Ensemble, formed in 1974 by George Tomov, former lead dancer in Yugoslavia's state ensembles Lado and Tanec. Tomov toured with his group to Yugoslavia, and his dancers observed a difference between what they saw European dancers doing and what they had known as folk dance. As group member Doug Shearer noted, ”When we found out [what we were doing] wasn’t the real thing, we went looking for it.”6

There is a consensus among scholars that the idea of the “real” or “authentic” is a social construct, and differences in the criteria by which each of these three generations judged material to be “authentic” is another element that distinguishes them (see Bendix 1997). For the first generation, authenticity resided in the musical sound and rhythm of the dances and in the characteristic gestures associated with them, elements they had internalized as young people. This allowed them to experience dances shaped by choreography as authentic. The second generation lacked a feeling for authenticity of sound and movement in their bodies and ears because they had not spent time within these folk music traditions. Thus, when they looked for the authentic dance and music, their guide was to see what “authentic” people did. This created impetus for travel and a personal, amateur ethnomusicology.

Going hand in hand with growing travel, more recorded music and folk instruments became available, and dancers became interested in playing instruments they saw folk musicians using. Forming bands around specific repertoire shifted the idea of a dance night from recorded music in many styles to dancing to live music in one. People wanted to dance as they did “in the village.” The East European Folklore Center was founded in 1982 with a summer camp on the West Coast in 1985, followed by a camp on the East Coast in 1986. From the beginning, the camp functioned as an incubator of sorts—expert musicians and singers, whether immigrant, flown in from Europe, or America-born, taught five out of six classes in five slots throughout the day. The sixth class in each slot was led by a dance teacher. Balkan Camp gave participants a chance not only to learn from the musicians they admired, but to form friendships and party with them. The schedule of Balkan Camp gave participants a taste and structure for their own events when they went home—daytimes for classes and practice, evenings for dancing to the music of teachers (like the parties of various ethnic groups), and musical nights at the Kafana (makeshit tavern) until 4 am, where teachers and students would jam and new bands could play.

The brass band Zlatne Uste was founded by Michael Ginsburg at EEFC East Coast Balkan Camp in 1983. In 1985, Zlatne Uste sponsored its first Golden Festival in one room at the Ethnic Folk Arts Varick Street location. Dancers went looking for live music, finding celebrations of immigrant communities and trying to dance along with them.

Example 2. Zlatne Uste Balkan Brass Band at Balkan Cafe, Hungarian House, New York City. [Published 11 April 2017]. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlpVzAsdt0s>

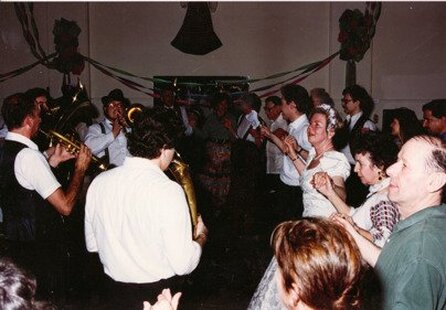

Illustration 3. Zlatne Uste playing for the author’s wedding at Hungarian House, NYC, 11 April 1996 (photos by Barbara Laudis, courtesy of the author).

Generation Three: The Millennials

The youngest group of music and dance enthusiasts is the most eclectic. They have many points of entry – many participate because of their parents, but others find their way through bar settings, concerts, recordings, YouTube, festivals, and college campuses. Sometimes they stay with that first experience, and only participate erratically. Jenna Shear, who grew up in the folk dance community and is now in her twenties, noted that this generation tends to focus on the current work of professional musicians within their traditions, rather than to worry about an earlier time perceived to be more authentic. This might include modern electronic equipment if that is what bands in the Balkans are using. As musicians, they are more willing to improvise and create a personal sound.

In comparing all of these groups, most striking is their way of interacting with dance and musical material. The first group preferred a dance that had been shaped for them by an expert, and they happily traveled to the places of origin of particular dances on tours organized by a dance leader. The second group was aware that their folk dances were not done as “in the village” and went to find those people and dances, but then they wanted to copy the dances exactly. Even Zlatne Uste memorized song tracks of various Serbian groups, sometimes characterizing themselves as a cover band.

The third group is more likely to accept the eclectic approaches of contemporary musicians and learn to improvise within a variety of idioms. For this generation, finding information has become much easier than the information-gathering methods of earlier groups. Jenna noted that her generation is so data and computer-based that they would feel very uncomfortable asking an expert about anything they had not thoroughly researched on the web first.

I also found intriguing differences in how each generation approached an ideal of “global harmony.” A number of people in the first group told me that after World War II they felt it was important to rebuild the idea of a world where people and countries could exist harmoniously, and they felt they were contributing to this goal through folk dancing. In tours to Europe they loved dancing together with local people even if they weren’t doing exactly the same steps.9

The middle group was much more active in seeking out immigrant groups and dancing with them—Greek festivals all over New York, and Bulgarian, Hungarian, and Armenian events, for example—trying to do what the dancers were doing but not necessarily learning any more about the groups they visited. The third group articulates a much more involved approach, of, “if doing what they do is the source of our joy, then we owe it to them to find out a little about their lives, and give something back—what they need.”10

Here, new bands are once more following the example of Zlatne Uste. In 1987, this band traveled to Guča in Serbia to participate in a festival of bands they were emulating. The trip involved considerable effort and not unsubstantial danger—audiences were suspicious of the Americans but accepted them when they showed they could play popular Serbian brass band music. Zlatne Uste’s participation in a later Guča Trumpet Festival is represented in the documentary Brasslands (2014). It is their willingness to meet other musicians on their own terms that inspired Zlatne Uste to contribute proceeds of the Golden Festival to relief organizations working in the Balkans.

This year a new group is making preparations to follow them to Guča—Čoček Nation. Čoček Nation was also formed at Balkan Camp, composed of the children of participants, led by Sarah Fernholt, a trumpet player from Zlatne Uste. This group teaches brass band music and improvisation to the youngest of players on any instrument, and every year it is the first to perform at the Golden Festival. Members of Čoček Nation have moved on to participate in other brass bands, such as What Cheer? Brigade, a prominent band of the HONK! movement.

OrnâmatiK from Ann Arbor is an example of a band that is steeped in the music preserved by previous generations of International Folk Dancing but is not afraid to meld it with other music that interests them. This openness to hybridity and fusion, in contrast to previous generations, allows young bands to find their own voices and brings them closer to the musically eclectic aesthetic of HONK! bands. At Balkan Camp, OrnâmatiK’s Kafana slot and those of their friends come somewhere around 2 or 3 AM and include jams with all sorts of instruments. Cellist Abigail Alwin noted that much of the music comes from the internet. Example 3 shows OrnâmatiK’s approach to improvisation, beginning with the Balkan model but branching out into other styles.

Example 3. Gankino - OrnâmatiK - Live @ Kafana 2013 [published 27 August 2013]. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V98SQUT1uJ4>

Nonetheless, the music of OrnâmatiK still works for traditional dance:

Example 4. Funky Balkan Party Yay! [published 23 December 2012]. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaw2mQLUEeo&t=75s>

A larger break from the past can be seen with the brass band Slavic Soul Party!. Matt Moran played with Zlatne Uste in the late 90’s and formed Slavic Soul Party! in 2000. Matt sees himself as more willing to tinker with the music. He spoke to me about how his approach differs from the attitudes he found with many of the people at Balkan Camp:

We play more in other venues where people aren’t as knowledgeable about the dances. The Balkan dances are amazing, deep, wonderful things, but to me it’s not as important to have everyone experience that mystical . . . amazing Macedonian dance experience as it is to have many more people dance, just dance, and have that joy of dancing with other people. . . Basically, I watched many audiences stop dancing because folk dancers came up to the front and showed everyone, like, how the dance should go. It just inhibited so many people who didn’t have that level of knowledge, inhibited them from dancing. . . So I just stopped really offering a folk dance experience as a part of what we do because I just felt like it was pushing more people aside than it was bringing people in. It was a hard thing to figure out when I am also so pro “music and dance should go together,” and “this is traditional.” And so eventually I had to go with what seemed the bigger, brighter thing to do.11

Matt’s loyalty to the way his newer and more diverse audiences respond, rather than to the older folk dancers, is one striking aspect of the change in bands and their relationship to new audiences for Balkan music. It is but a small step from here to taking brass band music out of the dance hall and into the street. What Cheer? Brigade has performed at Guča and many other music festivals in the US and Europe as well as Somerville’s and Providence’s HONK! Festivals every year since 2006, and the band has closed the Golden Festival for many years. It was built out of friends and acquaintances with some brass experience. Tubist Daniel Schleifer recounts that one of the main reasons What Cheer? Brigade chose the medium of brass was a sense that in order to be effective within the Providence R.I. scene they needed to be loud, certainly echoing the Serbian Roma bands they often emulate. Being able to play without amplifiers gave the band flexibility and immediate street-readiness.12

Daniel said the band “backed into” Balkan because the music was available for starting a brass band and because much of it is in minor keys and fits the band’s somewhat dark aesthetic. The band’s repertoire includes New Orleans favorites, Bollywood renditions, original pieces, classical arrangements including Erik Satie’s “Gnossienne, No. 1,” and Balkan brass band standards like “Jovano” and “Bubamara.” Daniel found his way to Balkan Camp and is now a part of that scene as well and has brought players originally based in IFD back to What Cheer?.

Example 5. What Cheer ? Brigade at Zlatne Uste Golden Fest January 17 2015 [published 18 January 2015]. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2n-Oa0RRJMg>

Illustration 4: What Cheer? Brigade and fans at Zlatne Uste Golden Festival, 19 January 2019 (photo by the author).

The cross-fertilization that now occurs between HONK! and the Balkan dance scene is bringing new repertoires and playing styles to both scenes. This study has revealed some of the transitions that occurred as International Folk Dance emerged into the current Balkan music scene in the United States, beginning with the sharing of heritage cultures through folk dance choreographies that everyone could learn and the growing popularity of line dancing to recorded music in the first generation. Dancers in the second generation took up instruments and focused on playing the music “authentically,” leading to the embrace of brass bands, as well as many other Balkan ensembles. The third generation brought a more diverse community to Balkan music with new uses for the music. Their anxiety about authenticity diminished in favor of bringing Balkan dance music to the clubs, the streets, and to the HONK! movement. In HONK! today, Balkan music collides and fuses with the vast musical diversity from throughout the world that bands bring to the festival.

References cited:

This article shares research with a presentation at the 31st Symposium of the Study Group on Ethnochoreology of the International Council for Traditional Music in Szeged, Hungary in July 2018. All video examples are referenced here with the URL of their original source, but they are repeated for this scholarly article at my YouTube channel, JudyOlson1, gathered in the playlist “ICTM 18 HONK! Examples.”

Bendix, Regina.

1997. In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Casey, Betty.

2000. International Folk Dancing U.S.A. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press.

Cohn, Lorraine S.

2018. “How Is Folk Dancing Evolving In the New York City Metropolitan Area?” (unpublished mss); received 15 July by email.

Derek Brown (YouTube username).

2017. Chichovata, Zlatne Uste Balkan Brass Band at Balkan Cafe, Hungarian House, New York City. NY; posted April 11. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlpVzAsdt0s>. Video examples have been copied to YouTube channel JudyOlson1 under ICTM 2018 HONK!.

Dino Dvorak (YouTube Username).

2015. What Cheer ? Brigade at Zlatne Uste Golden Fest January 17 2015, Brooklyn, NY; posted 18 January. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22). <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2n-Oa0RRJMg>.

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

Online: <http://www.socalfolk dance.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Ginsburg, Michael (consultant).

2011. Skype interview with Judith E Olson, Brooklyn, New York; 24 June.

Golann, Ellen (consultant).

2018. Phone discussion with Judith E. Olson, Woodbury, New York; 30 November.

Halper, Evelyn (consultant).

2018. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Rockville Center, New York; 8 June.

[Herman, Mary Ann]

1945. Welcome to Our Spring Open House Folk Dance Party! Flushing, LI, NY: Community Folk Dance Center; 25 May. Community Folk Dance Supplement, Flushing, NY: The Folk Dancer Magazine. Courtesy of Evelyn Halper.

Kungfudru (YouTube Username).

2012. Funky Balkan Dance Party yay! Ann Arbor, Michigan; published 23 December. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaw2mQLUEeo&t=75s>

kungfudru.

2013. Gankino - OrnâmatiK - Live @ Kafana 2013. EEFC East Coast Balkan Camp, Rock Hill, NY; posted August 27. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V98SQUT1uJ4>.

Lampell, Maurice (videographer).

2015 Ciuleandra danced at Ellen Golann’s Holiday Folk Dance Party Dec 25, 2015, Plainville, NY; 25 December, posted 29 November 2018, courtesy of Maurice Lampell. (YouTube video at YouTube Username JudyOlson1) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTcwhD9n8gY>.

Laušević, Mirjana.

2007. Balkan Fascination. Creating an Alternative Music Culture in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moran, Matt (consultant).

2011. Skype and phone interview with Judith E. Olson, 25 June.

Oakes, Dick.

International Folk Dancing.

Online: <http://www.phantomranch.net/folkdanc/folkdanc.htm> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Rahn, Monie (consultant).

2014. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Jericho, NY; 3 July; posted 1 October 2014. (YouTube video) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Z9o2QS61XI&feature=youtu.be>

Daniel Schleifer (consultant).

2019. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Brooklyn, NY, 20 January.

Shay, Anthony.

2007. Balkan Dance: Essays on Characteristics, Performance and Teaching

Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Shearer, Douglas (consultant).

2018. Phone interview with Judith E. Olson, Ramsey, New Jersey; 22 June.

Shear, Jenna aka Jenna Shearer (consultant).

2018. Messenger interview with Judith E. Olson, Arlington, Virginia; 2 July.

Society of Folk Dance Historians.

Online: <http://www.sfdh.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Stockton Folk dance Camp.

Online: <http://www.folk dancecamp.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Footnotes:

References cited:

This article shares research with a presentation at the 31st Symposium of the Study Group on Ethnochoreology of the International Council for Traditional Music in Szeged, Hungary in July 2018. All video examples are referenced here with the URL of their original source, but they are repeated for this scholarly article at my YouTube channel, JudyOlson1, gathered in the playlist “ICTM 18 HONK! Examples.”

Bendix, Regina.

1997. In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Casey, Betty.

2000. International Folk Dancing U.S.A. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press.

Cohn, Lorraine S.

2018. “How Is Folk Dancing Evolving In the New York City Metropolitan Area?” (unpublished mss); received 15 July by email.

Derek Brown (YouTube username).

2017. Chichovata, Zlatne Uste Balkan Brass Band at Balkan Cafe, Hungarian House, New York City. NY; posted April 11. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hlpVzAsdt0s>. Video examples have been copied to YouTube channel JudyOlson1 under ICTM 2018 HONK!.

Dino Dvorak (YouTube Username).

2015. What Cheer ? Brigade at Zlatne Uste Golden Fest January 17 2015, Brooklyn, NY; posted 18 January. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22). <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2n-Oa0RRJMg>.

Folk Dance Federation of California, South, Inc.

Online: <http://www.socalfolk dance.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Ginsburg, Michael (consultant).

2011. Skype interview with Judith E Olson, Brooklyn, New York; 24 June.

Golann, Ellen (consultant).

2018. Phone discussion with Judith E. Olson, Woodbury, New York; 30 November.

Halper, Evelyn (consultant).

2018. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Rockville Center, New York; 8 June.

[Herman, Mary Ann]

1945. Welcome to Our Spring Open House Folk Dance Party! Flushing, LI, NY: Community Folk Dance Center; 25 May. Community Folk Dance Supplement, Flushing, NY: The Folk Dancer Magazine. Courtesy of Evelyn Halper.

Kungfudru (YouTube Username).

2012. Funky Balkan Dance Party yay! Ann Arbor, Michigan; published 23 December. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaw2mQLUEeo&t=75s>

kungfudru.

2013. Gankino - OrnâmatiK - Live @ Kafana 2013. EEFC East Coast Balkan Camp, Rock Hill, NY; posted August 27. (YouTube video)(viewed 2018 July 22) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V98SQUT1uJ4>.

Lampell, Maurice (videographer).

2015 Ciuleandra danced at Ellen Golann’s Holiday Folk Dance Party Dec 25, 2015, Plainville, NY; 25 December, posted 29 November 2018, courtesy of Maurice Lampell. (YouTube video at YouTube Username JudyOlson1) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FTcwhD9n8gY>.

Laušević, Mirjana.

2007. Balkan Fascination. Creating an Alternative Music Culture in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Moran, Matt (consultant).

2011. Skype and phone interview with Judith E. Olson, 25 June.

Oakes, Dick.

International Folk Dancing.

Online: <http://www.phantomranch.net/folkdanc/folkdanc.htm> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Rahn, Monie (consultant).

2014. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Jericho, NY; 3 July; posted 1 October 2014. (YouTube video) <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7Z9o2QS61XI&feature=youtu.be>

Daniel Schleifer (consultant).

2019. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Brooklyn, NY, 20 January.

Shay, Anthony.

2007. Balkan Dance: Essays on Characteristics, Performance and Teaching

Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Shearer, Douglas (consultant).

2018. Phone interview with Judith E. Olson, Ramsey, New Jersey; 22 June.

Shear, Jenna aka Jenna Shearer (consultant).

2018. Messenger interview with Judith E. Olson, Arlington, Virginia; 2 July.

Society of Folk Dance Historians.

Online: <http://www.sfdh.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Stockton Folk dance Camp.

Online: <http://www.folk dancecamp.org/> (accessed 2018 December 13).

Footnotes:

- Laušević, Mirjana. 2007. Balkan Fascination. Creating an Alternative Music Culture in America. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 140. This study includes a thorough discussion of precursors to International Folk Dancing and its early years.

- Ibid, p. 156-166. See also Betty Casey, International Folk Dancing U.S.A. (University of North Texas Press, Denton TX, 2000), pp. 22-27.

- Evelyn Halper (resource person). 2018. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, 8 June, Rockville Center, New York.

- Lorraine S. Cohn, “How Is Folk Dancing Evolving in the New York City Metropolitan Area?” (unpublished mss) received 15 July 2018. Michael Ginsburg (resource person). 2011. Skype interview with Judith E Olson, 24 June. New York, New York

- Ellen Golann (resource person). 2018. Phone conversation with Judith E. Olson, 30 November.

- Douglas Shearer (resource person). 2018. Phone interview with Judith E. Olson, 22 June.

- Jenna Shear aka Jena Shearer (resource person) 2018. Messenger interview with Judith E. Olson, 2 July.

- Michael Ginsburg (resource person). 2011. Skype interview with Judith E Olson, 24 June.

- Monie Rahn (resource person). 2014. Video interview with Judith E. Olson, Jericho, NY, July 3, 2014.

- Jenna Shear, ibid.

- Matt Moran (consultant). Skype and phone interview, 25 June 2011.

- Daniel Schleifer (consultant). Interview 20 January 2019.